Aight so I am writing this on a Sunday morning equal parts frustrated confused and hopeful. Outside there is a continuous war going on as an establishment willfully kills people who look and sound like me, and that same establishment is slowly crumbling as we know it. This moment has brought to the forefront, among many many things, the importance of controlling our narratives and combating the propagandized manipulation of our history as it’s happening.

So what follows below is an old conversation about a film I love (Hale County This Morning, This Evening) with the man who made it (RaMell Ross), and more deeply about granting a visual honesty to Blackness through lens and on screen. The piece is something I should have published months ago but am finally publishing now, as it is more crucial than ever that we speak when we can still breathe and write when our hands can still move.

“Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time.” ― James Baldwin, “The Fire Next Time”

There is a three-ish minute long scene in the documentary Hale County This Morning, This Evening where a toddler, Kyrie, is moving — like something between jogging and waddling — in circles around his parents’ condensed living room. The camera is observing this at floor level and out of focus in the deep left center of the frame is a television. To the right are the legs of Kyrie’s parents, Quincy and Boosie, lounging in overworn sofa chairs staring at a blue-ish screen. In and out of focus is the pacing Kyrie, offering nothing but grunts and deep breaths over a bed of indistinct TV drama dialogue.

The scene’s relative silence speaks volumes. Kyrie is confined only by the blueprint of the space around him — the running symbolizes an infantile innocence of a Black child whose nascent dreams will one day grow bigger than those confines often allow. The young parents slouching in their chairs are that child who grows older and becomes stuck — in their ways and/or by the figurative walls of institutional racism and poverty.

Hale County takes place in Hale County, Alabama. Which is to say it takes place in the rural Black Belt south. Which is also to say it takes place in a space that most Americans have not bothered to give attention to, let alone a visit. I have not lived in the south but I have visited my Alabama and Florida roots enough to understand how omnipresent generational trauma can feel when you are standing on ancestral land.

RaMell Ross spent 8 years in Hale County and in a way, he has yet to leave. Ross, a self-described “military brat,” first went to Greensboro, Alabama in 2009 to help consult a friend on a two-week project, teach a short GED program and coach high school basketball. After forming a genuine relationship with the students and community, he eventually spent his time documenting the lives of two families and day-to-day of Hale County through a single point-and-shoot digital camera.

The result is a masterpiece — an hour and 15-minute slice of Black love, death, dreams and dreams deferred by the often impermeable confines of poverty in the Black Belt South. The film is continuously dissecting itself, posing questions it doesn’t claim to have the answer to and presenting new ones with each viewing.

It asks us to consider life, generally speaking, as a race against time, and understand that the plight of the doc’s two main characters Daniel Collins and Quincy Bryant is in them learning that defeat can arrive far before literal death. At the start of the film, Daniel and Quincy present themselves as two young Black men who both have hoop and football dreams respectively, which we see deteriorate as they grow older. As time persists unrelentingly, and morning turns to evening just as night turns to day, we realize that opportunity can be just as limited as the time we’re supposedly granted.

“I already have my troubles for today, so I can’t worry about tomorrow. So I can only take it one day at a time and just try.” -Daniel Collins

There is Blackness and then there is Blackness in the rural South, where the moonlight accentuates our sheen, and strips the remaining world of its color. Under both moon and sunlight, RaMell’s lens brings visual justice to Black skin and being. His understated approach also gives a bewildering density to stillness — stillness in motion and in each character’s life trajectory.

This film came out in January 2018. I’ve put it on eight times now and still haven’t really seen it. Since first watching, I spent over a year trying to track down RaMell. We eventually met at a Q&A hosted by the Underground Museum in Los Angeles some time last year and connected on the phone a few months later. Below is a lightly edited version of a conversation we had about his process and the visual production of Blackness.

MYLES: It feels like this film challenged a lot of audiences.

RAMELL: It's strange, when the film first came out and even now, if you look at some of the reviews, some people are like, what is this crap? Like I don't know what's happening? Why? What is there to watch? What are people talking about? And tons of people have walked out over the course of it at the many places it's screened. When we first started screening at film festivals, while it did premiere at Sundance and win an award and a couple other ones, by no means did it feel like it was going to be as impactful as it has been. It’s still not everyone's film. You know, people aren't necessarily open to the type of imagery or type of loose narrative for people of color. I don't know why people can't get down with it enough to finish it or think it doesn't have some sort of value.

MYLES: Yeah there’s a rarity in seeing this kind of honest Black humanity in film, and for people of color to be given this much room to breathe on screen. What was your process in achieving that?

RAMELL: It stems strictly and directly from my photographic practice. It was being in the historic south and wanting to photograph the students that I'm working with. But then, you know, being confronted with the historical power dynamics between communities and specifically communities of color and the photographer and knowing that, you know, a portrait is as much, if not more a portrait of the photographer than it is the person who's in front of the camera. Just wanting to look for strategies to deal with that imbalance. And through that effect, if people think deeply about the history of image making, you are confronted with the history of racism and you realize the way in which images have been used. You know, I like to say that photography and film are the technology of racism. They sort of actualize whatever is in your head. And if the person that's reading it is in a brain space where they're used to the “Black image” doing a certain thing, then that's exactly what the photograph, regardless of how it’s made, will do, specifically when it's made without an openness that allows there to be multiple ways of comprehending it.

MYLES: The person behind the camera has to come from the purest and openness of heart and mind.

RAMELL: It's about not determining the purpose of the image. Because when you predetermine the purpose of the image, you're giving the image a logic that's not free. And when you use logic, the logic of the Black image returns to slavery and it returns to this power dynamic.So you're constantly in this almost recursive dialogue with representation and the problem of it. It becomes kind of like chewing on your own body. This recursive conversation forces the need to constantly prove our value through the image and the only way is to make images that aren't about that at all. That means that they have to be open to misinterpretation. And historically, we make images that land very solely on a specific thing in order to control that. But then that's part of a conversation that's not as open as it needs to be.

MYLES You shot over 1,300 hours of footage that you ultimately cut down to 76 minutes. How do you maintain that honesty when you inevitably have to edit images into a reasonable time frame?

RAMELL: Well it's strange, the film was difficult to edit, but the moments that were selected were easy to stumble upon because it was like a time-based process of waiting for moments that were so personally indelible that they had to be in the film. You know, if you shoot for four days, then all of a sudden you finally come across a moment where you're in the right position and something whimsical but also symbolic and also spontaneous and all of these other adjectives happens, you kind of don't forget it, and so the second that happens, you know, that's on the timeline. The biggest revelation to me, in filming and thinking about it, is that the process of making films doesn't lend itself towards gathering moments that are this unique. And so you end up constantly reproducing the same types of moments to say different or similar things. But even worse, you don't allow for new meaning to come from moments. You pursue a type of logic, you pursue a type of image and you pursue a type of representational mode that is in that same dialogue we talked about before, because it's a time based process to get to the stuff that happens naturally in the family, you know.

MYLES: When did a narrative start to take shape for you? I mean, you're filming over five years, so when was it clear enough where you could say “This is what I want this film to be about and here's how I'm gonna make that work.”

RAMELL: It was pretty early on. I want to say about three months in I made a more traditional cut and it was really disappointing because it didn't feel good. And so with the edit and taking that traditional approach, at first I go back to all of my footage, it's only after three months and I kind of intuitively select all of the moments that to me were just images, but just images that had content that were really beautiful and unexpected or whatever. And I put those on a timeline and I had some music from a friend that I asked for who ended up being the person who did the score. And just kind of sloppily, intuitively put them together. And after watching for like two or three minutes, it was just so bizarrely moving. But everything would be contextualized, like these sort of peripheral moments that had some sort of allure. All of a sudden, to me it said more about my experience and Hale County and being with the community, than the attempt to organize something comprehensible.

MYLES: You mention the score. The ominous music in each scene carries the film in an entirely different direction. There are also moments of silence that are equally moving. What were you looking for when putting the score together and deciding where to place music?

RAMELL: Well, thinking about what the images were capable of inspirationally, I was most attracted to sound and music that draws something out or stresses or expand the image, but isn't there to support it, or isn't there to sort of carry it in like a more expected way? Like, you know, I started to think about the way that generally speaking, Black folks use music in film. It's rap, it’s R&B, it's still very familiar. And that familiarity places our image in a very familiar place, which was the same sort of logic as the past. The film was originally filmed in three months and it was imagined with every single scene having music like the first cut that I made. That was like 56 minutes long. There were like 10 songs. It was all kind of like a music video approach. And then we found that having it fully musical, sort of makes it a tone poem, quote unquote, which isn't a quote unquote documentary. But then also we took out some of the music because when you strip it away from some of the scenes and it's completely silent, then all of a sudden that contrast makes both a bit more impactful.

MYLES: Did you want people to be uncomfortable with any part of this film? Like face an uncomfortable truth?

RAMELL: Well, yeah, but not you know, not explicitly. It's not like I wanted, you know, “at minute 35 is when x y and z happens and affects the consciousness.” You know, it was more that I knew that there was a collective power to decontextualized images of people like myself because of the way in which our image has been built over time through images. So working with all of these different registers, it would produce something in the person at some point, especially if you're conscious about the meaning and symbols. My whole thing was like, how do we just make the film so that someone can make it through it? Like, who cares if they know the conceptual underpinnings or the grand theory of strategic formalism. If they can make it through, then I can't imagine that someone would go outside and see a young Black man or a young Black woman or themselves as a person of color, I can’t imagine they will look at those things the same.

MYLES: It’s done that for me. I'm sure it has for you, too. Being removed from that now, like physically removed from Hale County and those families, how has that changed how you interact with people and see the world?

RAMELL: Well, it's a really disappointing realization when someone understands the extent to which we've been conditioned to see the world. I have this really platitudinal saying that like to the con artist, everyone is a mark. You know, to the really, really conscious political activists, everything is a political act. The craziest thing that I've read, which I say to people a lot is like to even imagine representation you have to reproduce the problem. That to show Blackness, you have to reproduce Blackness and Blackness is a fiction. You know, like we are a kind of stereotype in a certain sense. Our history is embedded in our skin. Without our skin, there's no Blackness. Conceptually at least. We recognize race now before we attribute any sort of language to it, because it's the American visual constitution. And so how do you deal with that?

MYLES: What led you to Hale County, Alabama? And what made you stay?

RAMELL: I got there really out of sheer luck where I had a friend that was coming to Hale county to consult on this two week art project and he asked me if I wanted to come. And I was like, yeah. And when I went, a job opened up in a youth program that was working with the folks that he was working with. And I was also teaching a photo course for the two weeks. But I was like, man, I'd live here. I was going crazy into debt, photographing in D.C. I couldn't afford the rent and freelancing wasn't really lucrative. And I said [the South] is the place where I can gather my thoughts, pay off some debt. And this place is beautiful and interesting. Being there you realize that it's a fairly unknown daily existence, specifically through media because of its history and just the way that it's visually represented, it's represented in cliches.

MYLES: Was there a difficulty in leaving that space after so many years investing in it?

RAMELL: Well, I mean, I'm still there. I have a house there and I'm working on a new photo project there. I'm pretty dedicated to the South because it seems to be this neglected site. I think a lot of artists and a lot of makers tend to tend to skip over the south and go directly to the continent of Africa and are looking for a place to bring more meaning to our American identity. But I think that we should go home to the south. That's kind of the place that has never been truthfully unpacked because of its war. It's like a horror house based on our perspective and our experience and still quite probably the most whitewashed of our entire existence in America in that we've just constantly been in the shadow of the antebellum mansions.

MYLES: It's weird because this movie is not really resolute. There’s a sadness but it's almost a fulfilling sadness. You feel a sense of hope. It's such a unique grey area that I've never really experienced with a doc. Like these characters are victims, not by anyone’s doing, but just by circumstance and time. Like nothing really works out in the end and yet time continues so you’re kinda hopeful for what’s next.

RAMELL: It becomes bizarre to me to think about that specifically in the context of what making it [the film] is. I met Daniel and Quincy and many other people in the community working in this youth center and immediately just coming from a different social context, northern Virginia, different type of education, different everything I'm like, oh shit, you guys are brilliant. You guys can do anything. You guys can work in the government. You guys can be doctors. You guys can be lawyers. And the process of my expectations and my imposing those different realities of pursuit on them is mind-blowing. You realize that the way in which the education system is built there, it produces a very specific spectrum of people. And so you end up having to adjust all of your expectations in order to have those that you're working with maximize their abilities, or see their potential within the time frame that you're with them. Just devastating. Like you want to go into a school and say you can be anything that you want. But that's a long road, you know? Where are they at 16 already? Where are they at 18? And how are they preparing to do anything that they want? … They're not, you know? And unless you're willing to spend every single moment of your life ensuring that they make all the right decisions in their own house when they're with their friends as they're learning, they're going to fall into the statistical trajectory that their region and their local reality produces.

MYLES: It’s a very specific and muted sort of tragedy. How do you manage to portray that so honestly in the hour and a half time frame?

RAMELL: It’s a challenge because when you make films that show folks making decisions and kind of doing things out in the world and failing and succeeding, then you allow the viewer to cast judgment on them. You individualize and humanize them to the point where you don't question the system that put them in a position to make those decisions. You question the person who is choosing whether or not to go to school, or to feel that and not to feel this, when we can create a world in which those decisions aren't even there. But that's not what the film concentrates on, it humanizes the person in order to create a connection with them, in order to do the humanist thing.

MYLES: There’s an urgency to their existence. Like working at the catfish plant is what drives the economy in Hale County and an inner title in the film says “Daniel dreads it.” It's kind of like each character is trying to run from the fate that's lurking over their community. It connects them to the point where each is really racing against time. Some have already lost, some are still running, and Kyrie has yet to begin.

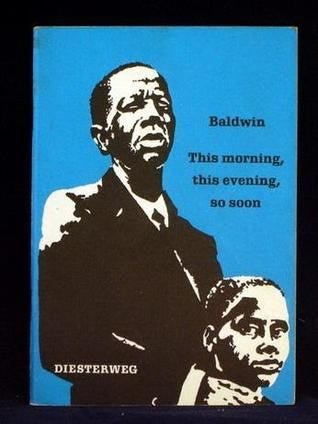

RAMELL: So the title of the film is Hale County This Morning, This Evening, part of that is taken from the Baldwin short story, which is called “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon.” There's some parallels between my identity and the main character who's living in Europe and going back home to the South to deal with this problem after being outside of a quote unquote “race culture” and dealing with those issues. But inside this film, you know, one of the inner titles after the eclipse is “So soon, Kyrie can reach the hoop.” And then you see the connection to what you're talking about, is that like the race against time is for Daniel and Quincy. And when their time is up, the race begins with their children. And then when that time is up, then it begins with the next child. Then based on our system, it's just there on that treadmill that Daniel is running on, where it’s cyclical and as the other sun drops in and the moon twirls, everyone's constantly running out of time and then placing their hopes, sadly but necessarily, into those younger who unfortunately are suffering the same ill.

“‘That's what it’s like in America, for me, anyway. I always feel that I don't exist there, except in someone else’s — usually dirty — mind.’” -James Baldwin, This Morning, this evening, so soon

MYLES: I tend to consider film and imagery in general as time capsules...

RAMELL: Definitely.

MYLES: And I think the ones that deeply resonate are those that you can put on however many years later and feel very present within the moment it was produced. This is one of those films. But how do you hope people consume Hale County retrospectively. Like how do you hope it's received and what it does for people?

RAMELL: That's my biggest fear, is making anything that only has a single use in that moment. I think that the more specific a tool is, the less power it has to be useful in the future. The film I wanted, and I think it's important for the idea of Blackness, is that like you and I know that we produce and expand Blackness every time we put on clothes or speak with someone in the street. Like someone looked at us as a Black person in conversation like “this is what Blackness is.” It's these interchanges, these glances. It's this constant expedition. But how do you make a film, then, that is open enough to constantly be read in the future? My theory, which I'm sure exists in many other people's writing, is that if you're going to call someone Black, then that means that when they call, it's a Black call. If they hiccup, that's a Black hiccup. But then you realize how absurd it is. It doesn't mean anything, but it means everything because you're attributing all of these characteristics to things that are nuanced.

MYLES: The question then becomes how do you translate that thinking to a common audience?

RAMELL: You can be an empath down to your bone marrow, but the only way to know what something is or what it's like, is to experience it. So how do we create work that is the experience of our centrality? How do we create work that is the experience of blackness? However nuanced, superficial, and expansive. And I think that's where work becomes timeless, because it's visceral. I'd imagine we'll have bodies for eternity. And I imagine that we'll have nerves and eyes and the sense organs. And so if you can use a camera in a way that gives someone that visceral sense of viewing, then you're allowing someone to participate in a perspective which is not theirs. It dissuades them from believing that their experience is the truth, because there's another one that they've also viscerally experienced, which therefore becomes two, which then can imagine there's more. And then there's a sort of attribution of validity to other people's issues.

—END—

hit me at…

twitter: @mylesaheadd | IG: @letitbreathe_

mylesduve18@gmail.com